Wild Thing: the story behind the Brick Works

The bucolic eco-paradise between Rosedale and the DVP almost never was. How big money and one ambitious entrepreneur remade the Brick Works

On May 29, the opening day of the Brick Works farmers’ market, I pedalled past the savvy people who had parked their cars illegally outside the Mount Pleasant Cemetery’s southern gate, knowing there would be no parking spots below, and through the Moore Park ravine. The air was cool and moist, the trees still. Then, the vista of the Don Valley opened up: the sun was shining on the pretty quarry garden, burning away the morning clouds and reflecting off the wetland ponds. I couldn’t yet see the market, but I could hear it: at 8 a.m., the site was already alive with happy chatter and the slow strum of “You Are My Sunshine” on guitar.

See a slideshow of the Brick Works, then and now »

I arrived to find bulrushes and Bugaboos framing the red brick buildings to the south of the quarry. It’s hard to imagine a more idyllic scene in Toronto, a city of mostly perfunctory landscapes, not known for its great beauty. In just three years, the organic market at the Brick Works has become the city’s largest, colonizing the once-abandoned factory of tumbled-down sheds and turning it into a utopian destination for a growing number of foodies. On this opening day, some 3,500 people came for the pastured eggs with marigold yolks, to sip organic fair-trade coffee and munch the city’s best GMO-free corn empanadas.

I wandered over to the native plant nursery, where a couple were debating the purchase of an apple tree, and bumped into an old friend who had come over from the Annex with his two kids. The boys were running circles around their dad, lobbying him for money to buy Belgian waffles. In a former industrial storage shed, dozens of vendors had set up tables, the farmers sprinkled in among the caterers and other producers. There wasn’t a lot of produce to buy (it was too early in the growing season), but there were plenty of other things on the tables. Ruth Klahsen of Monforte Dairy was selling her incomparable sheep’s milk cheese. At the other end of the shed, Jamie Kennedy’s son was tossing french fries in sea salt next to Andrew Hunter of Buddha Dog, who was selling his artisanal wieners. The organic farmer Ted Thorpe had lettuces at his table; sadly, no strawberries yet. You could get a 10-minute (and very public) massage if you were so inclined, or stock up on organic “muttballs”—chi-chi handmade dog food. But the wares almost seemed irrelevant. Not everyone was carrying bags on their way out; many were just there to catch up with friends and have their children’s faces painted by a volunteer. Elizabeth Harris, the market’s 67-year-old organizer, was sitting on a picnic bench serenely surveying the scene. She’d had a stroke earlier in the week and just got out of the hospital the day before, but she refused to miss opening day. Can you find Arcadia in a pint of raspberries, in a bouquet of organic lavender? The Birkenstocked mothers with their string bags seem to think so.

For decades, nobody knew what to do with the Brick Works, which sat forlorn and empty. There was something magnificent in the old, decommissioned brick buildings. In a city spectacularly unconcerned with its past, it was a spot to contemplate the ghosts of an earlier age.

Then Evergreen, an environmental non-profit, took over management of the site from the city. The Brick Works has been steadily insinuating itself into our consciousness ever since, and this month Evergreen will officially open its environmental community centre—the country’s largest—on the site. It’s an easy claim to make. Most environmental programs are pokey government operations—what Geoff Cape, Evergreen’s executive director, calls Ranger Rick facilities—which typically consist of a few signs about habitat preservation and a biology grad student to walk you around a pond. Cape has something much more slick and ambitious in mind. He hired a team of architects to build a five-storey, $15-million, LEED platinum building to house Evergreen’s headquarters, along with the offices of like-minded non-profits, such as Outward Bound Canada. There are classrooms to teach visiting schoolchildren and a conference space to host symposia on sustainability for CEOs. Most of the existing brick buildings have been shored up and re-roofed. Volunteers have planted native gardens and built an old-fashioned playground. Instead of shiny, permanent play structures, there are logs and water and dirt for kids to invent their own fun.

The Brick Works has all the elements to become one of the most exciting additions to our city’s landscape in decades. It offers the romance of city history (told through the old buildings and the artwork that will hang on the brick walls) and the tranquility of a nature preserve. Evergreen is changing the way we think about green spaces and one of Toronto’s greatest (if least celebrated) assets: our 11,000 hectares of ravines. Already, the Brick Works has become a place where strangers mix easily with one another, where people feel like they’re part of something worthwhile.

I grew up on the edge of the Rosedale ravine, in an ivy-covered muddy brick house built in 1927 on top of a decommissioned city dump by my architect grandfather. By the 1970s, our house was sinking into the valley at an alarming rate. The walls and floors became more cracked and tilted with every mud-softening spring. At times, it felt like there was no escaping the ravine or the family lore that kept us there long after my parents could afford the house. Even now I rarely fly in my dreams; more often I find myself at the bottom of a valley, floating in some deep, dark pool.

The ravine was my first playground, the place where my friends and I first tasted sap on the bark of maple trees, where we smoked our first cigarettes and kept our first trysts. Stinging nettles were a small price to pay for the thrill of exploring the edge of the unknown. We spent hours listening to the metallic crash of the city’s creeks as the water echoed through storm sewers and mixed with the familiar smell of concrete runoff. Some days we roamed even farther, to watch the river of traffic as it poured through the Don Valley just beyond the Brick Works.

The province was surprised that people cared about the brick works. and not just any people—people with money

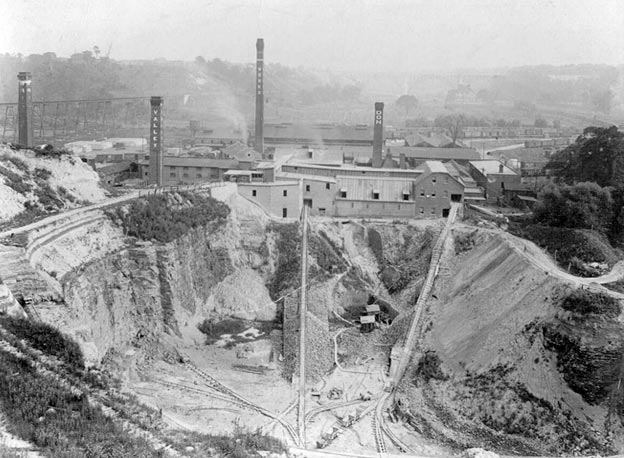

The factory sat at the edge of my playground, foreboding and off-limits, like some kind of industrial inferno etched by William Blake, belching smoke out of its chimney. We could feel the rumble of dynamite blasting clay and shale each morning, rattling the neighbourhood windows and shaking the ground. Although factory operations had slowed down by the 1970s, the kilns continued to fire bricks well into the ’80s. The 120-foot-deep scar of the quarry laid bare hundreds of thousands of years of geology.

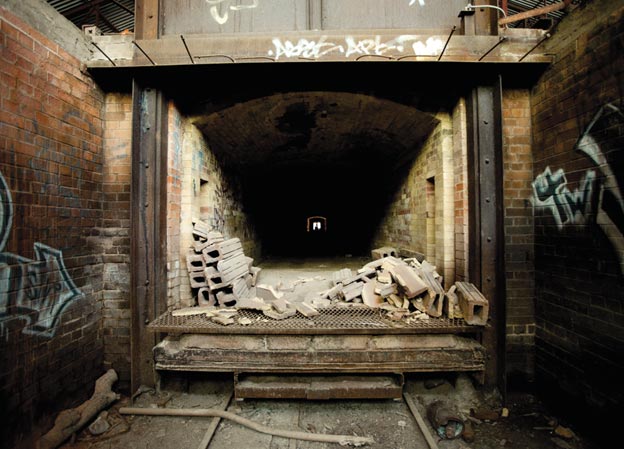

Before the first kiln was built at the Brick Works in 1889, people fished and swam in the Don River. Painters carried their easels down to the banks to work in the bucolic setting. The Great Fire of 1904 changed everything. In a matter of hours, entire blocks of buildings had burned to the ground. The city was a hollowed-out shell of its former self, and the demand for bricks skyrocketed. Out of the Brick Works, the city was reborn. The clay and shale of the quarry yielded many colours of bricks; iron-rich clay made the site’s famous cherry red bricks, which built the mansions of south Rosedale; limestone yielded the yellow bricks that Oscar Wilde ridiculed on a Toronto visit. By 1907, the kilns were the largest of their kind on the continent, with a daily capacity of 100,000 bricks, which baked for days, then slowly moved through the hot tunnels on conveyors.

As the quarry’s scar deepened, the chimneys belched more and more pollutants, and the runoff from the Brick Works killed fish and frightened away the last of the swimmers. Soon, the pleasure-seekers moved on to cleaner spots. By the 1970s and ’80s, only the very adventurous went to the Brick Works. A new generation of artists, among them the photographer Edward Burtynsky, came to record the decimation wrought by the open-pit mining.

In the ’80s, after most of the clay and shale had been quarried, the brick-making operation wound down, and a decades-long debate began over the future of the site. Should the quarry be filled and the flood plain developed into condos? Should the buildings be torn down and the landscape renaturalized? Or should they be restored and preserved as part of the city’s history? What people were really arguing about was the significance of our ravines and how we wanted to use them. Were they a preserve for animals or a place for people? Could they be both?

When the site went up for sale in the mid-1980s, Toronto’s conservation authority wanted to buy it. (The agency was formed to preserve the city’s watersheds shortly after Hurricane Hazel laid waste to the valleys in 1954.) But the province, which was to supply most of the funding, balked at the $4.1-million price tag. The land was instead sold to Torvalley, a property developer, which soon began trucking in landfill to patch up and level the quarry. Rosedale and Governor’s Bridge residents were horrified by the idea of a condo and retail complex in the Valley (and no doubt intent on protecting property values). They quickly formed a lobby group, Friends of the Valley, to block the looming development. Arguments were easy to make. Torvalley was planning to build the condos on a flood plain; you could still see the high water marks on the Brick Works’ shed posts—six feet high—from Hurricane Hazel.

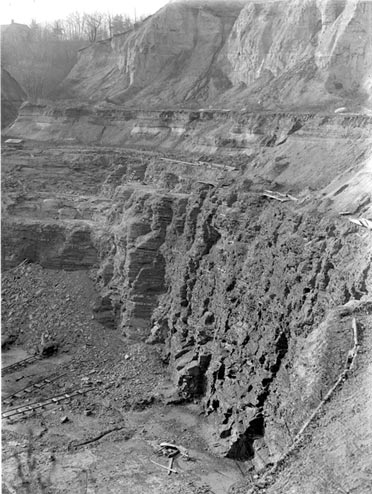

The province was caught by surprise: people cared about the Brick Works, and not just any people—people with money and connections. After years of legal wrangling, the province and the city shelled out $22 million to expropriate the property. The conservation authority would own the land and manage the green space; the City of Toronto was charged with the maintenance and preservation of the buildings. But nobody could agree on what exactly we were preserving. Nature conservationists wanted to pull down the sheds and let the Brick Works go wild. Architecture buffs were more concerned with preserving the factory buildings and protecting them from vandals and squatters. It was a tall order: the dozen or so buildings and sheds represented more than 200,000 square feet of floor space. There was even talk of founding a brick-making museum. Ed Freeman, a Friend of the Valley who lives in north Rosedale, is a retired geologist and local history buff; he was keen to preserve the north face of the quarry, which offers a rare look at four geological time periods. (It holds fossils of giant beavers and ancient pawpaw trees, if you know where to look.)

The authority commissioned the landscape architect Michael Hough to create a master plan for the site that would pay homage to both its natural and cultural history, but they couldn’t afford to implement it. Then Camilla Dalglish, a daughter of Garfield Weston and a staunch conservationist who had lived most of her life in a nearby house, stepped in. She was able to secure an $840,000 donation from the W. Garfield Weston Foundation in the early 1990s, and the money was used to implement part of Hough’s plan. Wetland ponds were formed, the boardwalks were built and grasses, wildflowers and trees were planted.

Even after the new gardens began to grow in, however, the acreage mostly sat empty. Conservationists saw this as a good thing, but it presented a problem. To protect something wild in the middle of the city, you need people. To paraphrase Jane Jacobs, you need eyes on the trees. Otherwise, the green space quickly becomes a dumping ground for garbage and a magnet for crime.

Glenn Garwood, until his retirement last spring, was the bureaucrat in charge of the Brick Works file at the city’s culture department. He couldn’t see any future in the site, at least not one the city could afford. (Years later, he still rolls his eyes at the idea of the brick-making museum. “Talk about a money loser,” he snorts.) His primary concern was liability. Squatters were living in the sheds, and you could see from the loops of spray paint that graffiti artists were scrambling over roofs and slipping in and out of broken windows. Raves and parties became a semi-regular occurrence. One night in October 2006, thousands of party-goers arrived in the pouring rain. There was live music and DJs. At one end of a shed, a group of shirtless teens roasted a pig over an open fire, pulling the flesh off the carcass with their bare hands. At the other, people lit Roman candles. It was a wake-up call for city hall. “All we needed was one kid to fall off a roof, and we’d have a lawsuit on our hands,” says Garwood.

The government had backed itself into a corner. To block the condo development in the 1980s, the conservation authority and its supporters had argued the flood plain couldn’t sustain any safe development. The province had also issued a heritage designation for the brick buildings. But to preserve them, they needed to be used; otherwise, they would continue to be vandalized.

The solution came in the form of Geoff Cape. Since Cape co-founded Evergreen in 1991, the organization has acted as a kind of eco-minded community builder in cities across the country; it raises funds for schools and works with them to plant native species on their grounds and create vegetable gardens to nurture young green thumbs. It also mobilizes community plantings and corporate volunteers, bringing them to public sites like the Brick Works to plant shrubs and trees. (Evergreen has more than 100 employees and 3,500 volunteers across the country.)

Cape has the self-assured air of someone who grew up in a well-connected family. Originally from Montreal, his ancestors made their money in construction and real estate, building the Montreal Forum and portions of the CN Railways, among other Canadian icons. His own connection with the natural world was shaped by weekends at his family’s 700-acre farm in Eastern Ontario. (He now lives in the Annex with his wife, Valerie Laflamme, and their three boys, ages eight, 10 and 12.)

I have never seen Cape wear a jacket or tie, even when he’s addressing a room full of suits at the Rotman School of Management, but he clearly inherited his family’s business savvy: he started a carpentry business while in high school, and at Queen’s University he sold houseplants, earning enough money in a few short weeks to cover a year’s tuition. Cape calls himself a social entrepreneur; he wants the Brick Works to pay for itself through revenue from event rentals, parking, plant sales and office leases, rather than depending on government handouts for support.

When Cape began lobbying the city and the conservation authority for control of the Brick Works in 2002, he was looking for ways to raise Evergreen’s profile and improve its bottom line. And Garwood was only too happy to listen to anyone who could take the site off his hands. Initially, Cape’s idea was a modest one: to establish a native plant nursery at the Brick Works so that Evergreen could grow its own seedlings and saplings, rather than buying them from someone else. He figured he needed $1.5 million to launch the project. But the more he thought about the site, the more ambitious his plans became. He began floating the idea of a large environmental community centre.

One of the many friends he spoke to was Kelly Meighen, a philanthropist who manages the T. R. Meighen Family Foundation. He told her about his expanded plans; to do it well, he’d need $10 million. She eventually promised him $650,000 and introduced him to David Young, the oil and gas investor, financier and philanthropist who funded Soulpepper’s new home in the Distillery District. They found a sympathetic audience: Young had been driving past the Brick Works for years, wondering why it had been left empty and rundown. “I’d think, Oh my God. Nobody in this city understands what’s here,” he says. “It was one of the greatest undiscovered secrets in Toronto. It’s sitting there, a mile away from downtown, from 50-storey skyscrapers. People can fish there, for God’s sake.” Shortly after meeting Cape, Young promised him $3 million.

After that, the donations started pouring in. The province pledged $10 million. Then the philanthropist Nancy McFadyen and other Cape supporters arranged a meeting with the new conservative government, which earmarked another $20 million for the project.

Cape smartly pitched the project as a way to promote community building, which was appealing to both government officials and hilanthropists—it seemed less elitist than funding cultural institutions like the AGO and the ROM. “Without being too excessively ambitious at this point,” Cape says earnestly, “I hope the Brick Works plays a prominent role in helping Toronto define itself in the future. To some degree, that is its big agenda.”

The greatest challenge was to get Torontonians to see the Brick Works as a place to congregate. Most community centres are in residential neighbourhoods; the Brick Works is nestled in a no-man’s land.

In 2007, farmers’ markets were just becoming popular in Toronto, and Cape reckoned launching one at the Brick Works might make Evergreen’s environmental message—that green spaces can make cities more livable—more appetizing to the mainstream. The 100-Mile Diet had come out earlier that year. All over the city, local food groups were mobilizing, and new farmers’ markets were opening weekly. Slow Food Toronto was gaining momentum; churches and synagogues and community centres were distributing boxes of produce from family-run farms. On a recommendation from Jamie Kennedy, Cape asked Elizabeth Harris, the founder of the Riverdale Farm market, to organize a trial run in one of the brick sheds on a cool Saturday morning in May.

Nobody at Evergreen was prepared for its success. Most of the farmers who showed up that first day did it as a favour to Harris; they certainly didn’t expect to be sold out by 10 a.m. By August, it had become the largest organic market in the city, and by the end of the summer, the number of visitors to the site had quadrupled. Suddenly, Rosedale dog walkers were mixing with Riverdale tree huggers. Early adopters were biking over from Trinity-Bellwoods and Dundas West. And when the parking lot filled up, north Toronto types parked their SUVs illegally on the shoulders of the Bayview Extension. Soccer moms were bushwhacking through poison ivy to get their fancy red carrots.

“Food really was an accident,” says Cape. “We stumbled into it.” Perhaps, but his timing was impeccable. Evergreen had bought into one of the city’s hottest grassroots movements.

Encouraged by the success of the farmers’ market, and later by the success of the Picnic at the Brick Works—a joint fundraiser for Slow Food Toronto and Evergreen that pairs up chefs and producers who hand out food samples to a sold-out crowd of 1,100 or so diners each year—Cape and his team have steadily added more and more food programs to their plans for the Brick Works. This fall, a year-round local, sustainable café and a takeout counter will open. Initially, Jamie Kennedy was expected to run the operation, but Brad Long of Veritas stepped in when Kennedy’s business was on the verge of bankruptcy. There are now community food gardens tended by staff and volunteers; wooden hives house roughly a million bees, and there’s a long waiting list for would-be beekeepers. Evergreen alone has 450 volunteers at the Brick Works, who put in a collective 3,000 hours last summer.

The brick works is changing how we think of parks, combining the romance of history with the tranquility of nature

In an earlier age, Toronto would have torn down the brick sheds, but we are beginning to see new value in these old places. We don’t just come for the food or the chit-chat with a charming artisanal cheesemaker. We also come for the worn-down bricks and the history immersion. We crave these historic buildings that can root us in our city’s past and tell us where we came from. The fashion for ruins was also hugely popular in 18th-century England. Back then, people were leaving the land to work in factories. Similarly, as our factories close, we’re developing a nostalgic appreciation for manufacturing.

This summer, Evergreen moved from Adelaide and Spadina to its new office on the site. Greenways (bulrush-filled canals) between the buildings will help ease flooding; bridges over the greenways will connect the buildings, just as the city’s bridges over our ravines connect our neighbourhoods. But even after spending $55 million, some of the site remains in ruins. One day, Cape plans to use the 350-foot-long tunnel kilns as an exhibition space for artists, but not yet; there was only enough money in the budget to make the kilns structurally safe.

Ever the optimist and a master of spin, he argues this is a good thing. He wants Toronto to have its own stake in the site. Throughout the summer, Evergreen hosted weekend community builds, employing volunteer manpower to finish the job. It’s a model borrowed from Evergreen’s first tree-planting events: once someone has planted a tree (so the theory goes), they’ll always have a proprietary interest in that patch of dirt.

Not everyone shopping at the farmers’ market is going to buy into Evergreen’s idealistic vision for a green shift in the city’s consciousness. People are biking and walking to the Brick Works—not necessarily because they’re giving up their cars, but because they know they’ll never score one of the 368 parking spots. Many people come because they crave a cone of Kennedy’s thyme-scented french fries or because their kids like getting their faces painted. But getting people there—by whatever means—is Cape’s greatest achievement. He trusts that the green part will follow naturally, as we venture out of the Brick Works and into the surrounding valley.

As I prepared to leave the market on opening day, I walked past two kids playing inside a man-made beaver lodge. “Let’s go hunting for turtles!” said the boy as he tugged his sister behind him. A gaggle of adults dutifully followed them back to the ponds in the quarry. Back to the ravine. Back to the garden.

It would be really great if the Brick Works site was integrated more with the surrounding trails/bike paths in the ravine, because getting there by car is not always practical or viable for everyone and the site is not served by transit. It would be also be nice if the Lower Don Trail and the ravine weren’t separated by Bayview, but that’s probably a different issue.

I agree a busroute would suit me as I cannot ride a bike nor do I have access to a car other than cab. At the current cab rates are ridiculous 450 in the door would not make it feasible for me. I think it would be more accessible to the public this way through TTC. Perhaps they should contact the TTC and try to get a route made up.

The TTC already has shuttles that take you from Davidsville station and Broadview Station to the Brick Work, no? I’ve taken it a few times.

They have a shuttle bus that goes from Broadview station direct. Not sure where you would the info on how often it runs but I happened to be by there a few weeks ago and saw the shuttle. I’m sure if you went to their website you’d find info.

If you go, do not park on Bayview Street! When I went there the cop had a field day and must have given out at least 50 tickets for illegaly parked cars.

The parking lot was very crowded. The site does not have the infrastructure to support the number of visitors that it gets.

There is a free shuttle that runs on weekends from Broadview station to the Brickworks and back. It runs approximately every 30 minutes between 9am and 5pm I believe.

Also you can take a TTC bus from Davisville station to the Brickworks. There is a TTC stop right in front of the main entrance.

It is a shame the only motivation mentioned for a brick making museum was revenue generation. Not an interest in telling the story of Toronto’s history (from perspectives that represent its diversity) nor discussing the very human impacts – good and bad – of large scale industrialization on the world. There are many here and abroad who continue

to suffer these impacts.

Historic sites offer the potential to look critically at how the choices we’ve made in the past have created the world we live in today.

I would like to see public-private partnerships such as the Brickworks (which is approximately $30 million government funded)take on more serious projects like good transit, water pollution, wildlife conservation, etc.

“The authority commissioned the landscape architect Michael Hough to create a master plan for the site…but they couldn’t afford to implement it. Then Camilla Dalglish, a daughter of Garfield Weston and a staunch conservationist who had lived most of her life in a nearby house, stepped in…the boardwalks were built and grasses, wildflowers and trees were planted.”

As a former Guelphite and current Torontonian I was thrilled when I opened up the September edition of TorontoLife to find that there was an article about the Don Valley Brick Works. However, upon reading the article I was disappointed to find no mention of the Guelph-based landscape architecture firm The Landplan Collaborative Ltd. in connection with park. What this article (and all others regardnig the Brick Works) fails to mention is that when Hough’s plan was too expensive to implement, a call for entries was made for the detailed drawings and among the firms to enter were Hough’s as well as Landplan. It was Landplan’s design that was selected and their drawings actually deviated almost entirely from Hough’s design. Landplan and its team of sub-consultants was responsible for the detailed design, working drawings and construction supervision for the extensive and popular Weston Quarry Garden located behind the factory buildings. What we see as the Brick Works today is not simply a design by Hough that was funded by the Westons.

For its contribution to the Brick Works Park, Landplan was the recipient of both a City of Toronto Urban Design Award and The Aggregate Producers’ Association of Ontario Bronze Plaque Award in 2000.

My expectation from a magazine known for its award-winning journalism is reliable and accurate reporting which I hope to see more of in the future. Let’s try and not forget the little guy next time, especially when in this case they really were the big guys in town.

Pretty great post. I simply stumbled upon your blog and wished to say that I have really loved surfing around your weblog posts. In any case I抣l be subscribing on your feed and I am hoping you write once more soon!